This entry is dedicated to the memory of our daughter Anna, z"l, who died two years ago, Het Nissan. May her memory be for a blessing.

Robert Frost said, "In three words I can sum up everything I've learned about life: it goes on." He knew what he was talking about. He outlived 4 of his 6 children. He outlived his wife. And his only son to survive childhood died by his own hand. Robert Frost lived to be an old, old man, teaching and writing and traveling. Life goes on.

It's been two years since our beloved Anna died. We think of her every single day. We miss her terribly. We grieve, usually in private, sometimes, unavoidably and mercifully rarely, in public. We go on.

This loss feels like an amputation. Like an amputee, I have lost, permanently, something valuable and irreplaceable. Like many amputees, I've learned to limp onward, figuring out how to manage and do things and go on with life in spite of the loss. Sometimes I manage so well that if someone didn't know, they might never guess that anything was missing.

Comfort comes in unexpected places. As a Jew, I find strange comfort in the book of Job. If you ever want to stop wallowing in self-pity, read Job and you'll gain some perspective. I read it over and over last year, feeling at one with Job's challenging, cursing, and even threatening God. Like Job, I could stand there in my integrity before God and say, "I did not deserve this, and Anna did not deserve this, and none of us did anything to deserve this" and know, as everyone who reads that first chapter of Job knows, that Job did nothing to deserve his suffering, that it all was planned on a cosmic level, that Job was, in God's own words, "אִישׁ תָּם וְיָשָׁר יְרֵא אֱלֹהִים וְסָר מֵרָע—a man pure and upright, fearing God and turning from evil. Comfort lies in the fact that God answered Job; God cared enough to appear in that whirlwind; God showed up.

We parents take a lot on ourselves. Though I believe we should, if life is going to go on, we eventually have to put down this burden o f guilt. Not only is it too heavy to carry around, it's presumptuous. Such suffering and pain as Anna felt are so huge that it's arrogant to think I'm at the center of it all. I knew this, but of course I blamed myself anyway, and the pain of loss was sharpened by the pain of responsibility.

But God justified Job to his friends (with their insidious accusations that I think must have been the products of Job's own conscience), and that justification must have been a strange comfort to Job, just as hearing Anna's wise and gentle therapist Dafna tell me, "Sue, you're not as important as you think; this isn't all about you" was a relief to me. Ultimately, it wasn't Job's fault, and it wasn't mine, and it wasn't Anna's either. As a mother, this is another strange place I find comfort.

After two years, the blame is, unbelievably, diminished. What isn't diminished at all is the pain of missing Anna. I read in a novel just the other day about a mother who missed her daughter, off in Europe. The mother, Isobel, thinks about her daughter: "She was impossible. She was also sweet, kind, funny, and overflowing with love. Isobel missed her quite dreadfully." I miss Anna quite dreadfully. She was sweet, kind, funny, and overflowing with love, and she was also impossible. How proud she would be of her siblings—whom she called "the creatures" (in the most loving way)--of Benjy's learning to read, and Jesse's following in her own footsteps in Tae Kwon Do (he periodically takes out her medals to admire, dreaming, perhaps, of getting his own), of Becky's budding acting career and Lulu's straight A's and mastery of Arabic. And Josh, her adored younger brother, standing in his army uniform. It hurts that she is missing all this. So many times I would have turned to her and shared a knowing smile, waited for her subtle insights, her quirky humor, and that sparkle in her eyes when she'd come home from a good day (she had many of these). "Anna," I'd call, "is that you?" And she would say, "It is I!" I am comforted by good memories.

For me, though, the greatest comfort lies in that meeting place between God and man, between what we see and what we can know when we stand on earth and look at the sky. An odd place to look for comfort, really, when most of what we see is dark and cold and unbelievably distant. Why, too, should we look to God for comfort? We want to hear God's voice, we want to feel God's presence, but God is—to quote Professor Uriel Simon-- generally silent. Or, like those glittering stars, cold and unbelievably distant.

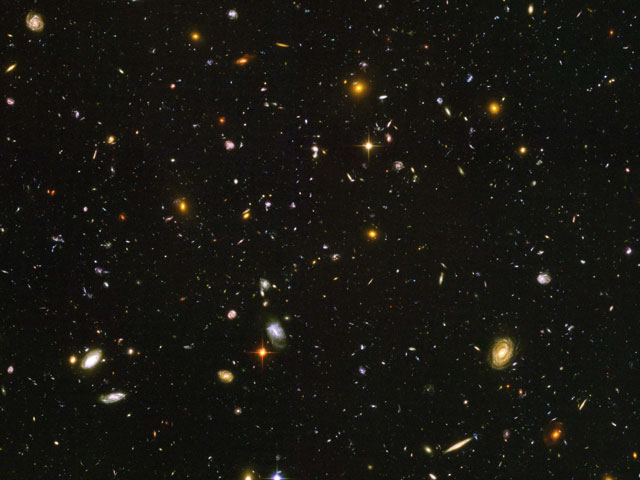

Yet astronomers know that the sky blazes with spectacular beauty in its darkest corners. When scientists sought out the most distant objects in the universe, they pointed the Hubble telescope at the emptiest, blackest section of the sky, an area without any stars or light, a veritable abyss as dark as the loss of a child. They did this so that the stars of the Milky Way galaxy would not hide with their glare what was really out there, invisible from our perspective on earth. What they found, of course, has been immortalized in the images of Hubble Deep Space and Ultra Deep Space—the galaxies of unimaginable shape and multitude and beauty that are revealed to us only because they lie precisely in the darkest parts of the sky we see from earth.

Job's final response to God has been characterized as one of meek acceptance of his lowly place in the cosmos. But to me, it rings not with resignation and acceptance but with profound understanding and awe. He speaks of נִפְלָאוֹת מִמֶּנִּי, וְלֹא אֵדָע –wonders greater than I am, that I didn't know, now revealed to his eyes.

Like Job, we will never understand the reason for suffering, but we know that there was meaning to all of it. We look at the sky and we remember that what is to our eyes the blackest and most empty part of the sky contains within it light and beauty, wonders greater than we are.